Olof Palme... and Bruce Springsteen!

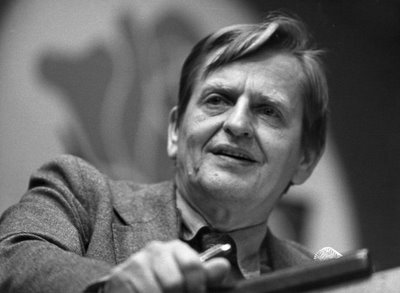

Today it is 20 years since Sweden’s Prime Minister and the Social Democratic Party’s chairman Olof Palme was assassinated in central Stockholm. You will find articles about Olof Palme’s life, his political legacy, and the unsolved murder everywhere in Swedish media. But I also found an AP story in The Washington Post and The New York Times, and an article in Le Monde.

Today it is 20 years since Sweden’s Prime Minister and the Social Democratic Party’s chairman Olof Palme was assassinated in central Stockholm. You will find articles about Olof Palme’s life, his political legacy, and the unsolved murder everywhere in Swedish media. But I also found an AP story in The Washington Post and The New York Times, and an article in Le Monde. When I was eleven years old, in the 1985 election campaign, I managed to get my father and grandfather to drive me to a public meeting where Olof Palme held a speech. The meeting was in the city of Solna just outside Stockholm and I can still remember sitting amazingly thrilled on a bench made of wood, waiting for Palme to arrive. And all of sudden he walked up on the stage in front of us, and I am pretty sure he had the speech in a plastic bag. At least my father used to joke about that, even several years later.

When I was eleven years old, in the 1985 election campaign, I managed to get my father and grandfather to drive me to a public meeting where Olof Palme held a speech. The meeting was in the city of Solna just outside Stockholm and I can still remember sitting amazingly thrilled on a bench made of wood, waiting for Palme to arrive. And all of sudden he walked up on the stage in front of us, and I am pretty sure he had the speech in a plastic bag. At least my father used to joke about that, even several years later. I remember election night 1985 vaguely, partly because my dad used to tell me how I lectured him about the functions of the Swedish electoral system (yes, I was a political nerd already then). I remember the night when Palme was shot, of course. For some reason my aunt lay awake the whole night listening to the radio; she called my family as soon as she heard the terrible news. The next day we went into Stockholm, just like so many others, in order to leave some flowers on the sidewalk where he was shot.

I remember election night 1985 vaguely, partly because my dad used to tell me how I lectured him about the functions of the Swedish electoral system (yes, I was a political nerd already then). I remember the night when Palme was shot, of course. For some reason my aunt lay awake the whole night listening to the radio; she called my family as soon as she heard the terrible news. The next day we went into Stockholm, just like so many others, in order to leave some flowers on the sidewalk where he was shot.Due to a lot of reasons I did not become a member of Social Democratic Youth when I turned 14 a couple of years later. That is another long story. It was not until the late 1990s until I found my way into the Social Democratic movement through student politics. But ever since that meeting in Solna almost 21 years ago, Olof Palme has been my major source of political inspiration. The main reasons are the same as for so many others: his hungry heart, beating for international politics, his fight against apartheid and all his other fights against oppression and injustices, his rhetorical skills.

This morning I put some roses on his grave, just like I do every year when I am in Sweden on the 28th of February. But I will not try to interpret his political legacy or retell stories others have already told - and/or experienced first hand. Others, who knew him, worked with him or have studied his legacy from an academic point of view, do that much better.

This morning I put some roses on his grave, just like I do every year when I am in Sweden on the 28th of February. But I will not try to interpret his political legacy or retell stories others have already told - and/or experienced first hand. Others, who knew him, worked with him or have studied his legacy from an academic point of view, do that much better.My contribution will only be the memories above, and this following quote. Thanks to my wonderful sister Anna, who recently found this speech by coincidence, I now know that my worlds match even better: in the speech Olof Palme speaks about Bruce Springsteen at length! I had never heard of this speech before, in which Palme is mixing politics, rock’n’roll and the importance of youth involvement. So, for all Swedish-speaking fans of Olof Palme and Bruce Springsteen out there, please enjoy.

Olof Palme under en debatt i Sveriges riksdag om den ekonomiska politiken, tisdagen den 11 juni 1985:

Sedan till en helt annan sak. Många talar om de svåra tiderna. Men slagregnet återföljs ofta av regnbågar. Och regnbågens skönhet förjagar minnet av slagregnet.

I lördags och söndags samlades över 120 000 unga människor till rockkonserter i Göteborg. Jag har hört bekanta som var där berätta om en enastående upplevelse, om en energisk, himlastormande gemenskap i musik och dans, om en fest i glädje och rytm. Från scenen sändes ljudet ut med en oherrans massa watt. Den mänskliga energin kunde mätas i ännu större tal. Lite lakoniskt meddelade Göteborgspolisen att det var en lugn helg.

I lördags och söndags samlades över 120 000 unga människor till rockkonserter i Göteborg. Jag har hört bekanta som var där berätta om en enastående upplevelse, om en energisk, himlastormande gemenskap i musik och dans, om en fest i glädje och rytm. Från scenen sändes ljudet ut med en oherrans massa watt. Den mänskliga energin kunde mätas i ännu större tal. Lite lakoniskt meddelade Göteborgspolisen att det var en lugn helg.Ibland – oftare än vad som sker – är det befogat att här i riksdagen ge de unga människor ett erkännande som det annars för oss äldre är så lätt att smutskasta, som ofta förstår så mycket mindre än vi anser oss begripa.

När Bruce Springsteen gjorde en paus, efter en och en halv timmes musik, kom störtregnet, ackompanjerat av en regnbåge. Solen letade sig fram med sneda kvällstrålar över de tiotusentals väntande ungdomarna på fotbollsplanen.

Då kom Bruce Springsteen in igen. Han sjöng om arbetslöshetens och de sociala orättvisornas störtregn i ”Johnny 99” – den sång som han uppmanat Reagan att lyssna på – och han sjöng om arbetarungdomarnas hopp och drömmar.

Då kom Bruce Springsteen in igen. Han sjöng om arbetslöshetens och de sociala orättvisornas störtregn i ”Johnny 99” – den sång som han uppmanat Reagan att lyssna på – och han sjöng om arbetarungdomarnas hopp och drömmar.Jag vet inte hur mycket vi i vår generation förstår av denna musik och av dessa texter. Men de som talar om de unga som förtappade odågor har fel. Och de som missar krusningen i den anpassliga masskulturens mest kolorerade media för ungdomarnas faktiska inställning har också fel.

I själva verket är det säkert nu som det alltid har varit: Ingen upprörs så av sociala orättvisor som de unga. Ingen finner det i grunden så felaktigt som de unga att det skall behöva finnas arbetslöshet. Och ingen drabbas heller hårare av arbetslöshet eller är värnlösare mot orättvisor än de unga.

Därför känner jag ett behov av att säga att vi måste – och kan – tro på de unga. Frågan är vilket samhälle som förtjänar de ungas tilltro.

I mitt första anförande beskrev jag det goda samhälle som vi socialdemokrater strävar efter, där det finns jordmån för generositet och där det finns plats för alla.

I mitt första anförande beskrev jag det goda samhälle som vi socialdemokrater strävar efter, där det finns jordmån för generositet och där det finns plats för alla.I bjärt kontrast till detta samhälle står det konkurrens- och konfrontationssamhälle som man verkar tala om. I ett sådant samhälle måste människorna ständigt bekämpa varandra. I den kalla egoismens samhälle blir varje människa en medtävlare och ett tänkbart hot. Ur detta föds misstro och misstänksamhet.

Vi socialdemokrater säger nej till den sortens samhälle, som i längden blir isande kallt och ödsligt att leva i. Vi säger nej till den begränsning av den enskildes möjligheter som orättvisor och otrygghet innebär.

Vi säger ja till den solidaritetens och demokratins samhälle där fria människor gemensamt, i ömsesidig respekt och under ömsesidigt ansvarstagande, formar en tillvaro där alla har lika möjligheter och lika värde. Vi säger nej till ”systemskiftet” och ja till att värna och förnya folkhemmet!

(Bilder på OP från AiPs bildarkiv)